The Mwanza Intervention Trials Unit (MITU) based at the National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR) campus in Mwanza, Tanzania is a collaborative research unit of NIMR and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. The mission of MITU is to contribute to improving health through the development and evaluation of interventions against infections and other health problems by conducting research, including clinical trials, to the highest international standards. MITU also aims to enhance the capacity to carry out such research in Tanzania and to contribute to the translation of research findings into health policy. The Unit is now inviting applications from motivated and suitably qualified candidates to fill the following position that will be based at NIMR campus, Mwanza.

Position: Senior Finance Officer

Ref. Number: MITU/FIN/01/21

We are seeking to appoint an ambitious and highly motivated senior finance officer with proven technical experience in accounting and financial management, who is capable of working under the supervision of the Associate Director of Finance and Administration as part of the finance team of MITU.

Principal responsibilities

- Be responsible for managing all finance aspects of various projects, including preparing quarterly management accounts and providing day-to-day advice, guidance and support to MITU’s Principal Investigators (PI’s) and Project Co-ordinators (PC’s).

- Maintain and update MITU’s financial systems and controls, verifying and checking the financial records, reports, ledgers and statements.

- To support with the preparation of audit files during audits, liaise with staff and auditors during the process and help prepare supporting documentations and the production of audited annual accounts.

- To be responsible for the processing of sales invoices for grants and other income sources, thereby ensuring that all monies are received and banked accordingly.

- To maintain appropriate computerised and paper filing systems of financial information in accordance with MITU’s process and procedures.

- To manage the MITU fixed asset register in collaboration with the procurement team, thereby ensure that this is fully updated.

- To assist Investigators during proposal budget preparation and to also help with setting up of budgets within the MITU finance systems.

- To assist with the monthly payroll, including the reviewing of overtime claims forms and ensure that all overtime claims are accurate and in line with MITU’s processes and procedures.

- To provide financial information and advice to other MITU colleagues as and when required.

- To liaise with MITU senior staff and collaborating institutions on any administrative issues.

- Promote MITU, its core values and services, and play a positive role in the delivery of its day-to-day operations and strategic goals.

- To carry out other duties relevant to the post as and when requested.

PERSON SPECIFICATION

Essential criteria for selection

- A relevant accounting qualification, degree in Accounting, Finance, Business Administration or a professional accounting qualification (CPA/ACCA or equivalent).

- A minimum of 5 years experience working within a similar organisation preparing management accounts using computerised software packages.

- Excellent financial software knowledge such as ERP Navision, SUN, QuickBooks.

- Excellent financial report-writing skills and the ability to communicate financial information easily to be understood and in a clear format.

- Proven experience of preparing and monitoring budgets and financial reports.

- Strong organisational skills with proven ability to work effectively within a team, assess priorities and manage workload with minimum supervision.

- Proven experience of good written and oral communication skills in English.

- Experience of managing restricted/unrestricted income and expenditure accounting and reporting.

- Experience of managing grants from international Donor such as DFID, ERC, MRC, USAID etc.

- Self-motivation and effective time management skills.

- Excellent communication and interpersonal skills.

Desirable criteria for selection

- Experience of working within the development sector e.g., Non-governmental Organisations (INGO’s or NGO).

- Experience of working within a Research Institution/Organisation.

MODE OF APPLICATION

E-mail applications to recruitment@mitu.or.tz with the following:

- Detailed supporting statement/letter – Whereby each section should set out how your qualifications, experience and skills meet each of the essential and desirable criteria within the person specification. Please provide one or more paragraphs addressing each criterion. The supporting statement is an essential part of the selection process and thus a failure to provide this information will mean that the application will not be considered. An answer to any of the criteria such as “Please see attached CV” will not be considered acceptable.

- Please include a daytime mobile telephone number and e-mail contact details.

- Curriculum vitae (CV) including names and addresses of two referees (one must be from your most recent employer or training institution).

CLOSING DATE FOR APPLICATION

- Applications received later than 26th February 2021 will not be considered.

- You will be informed by email if selected for interview and only shortlisted candidates will be contacted.

- Interviews will be held in the following weeks at the NIMR Mwanza Centre, Isamilo, Mwanza or remotely through zoom or other online platform.

According to studies, intimate partner violence – defined as physical, sexual or psychological harm by a current or former partner or spouse – is the most common form of violence experienced by women in relationships throughout the world. It is estimated that about one in every three women worldwide will experience physical or sexual violence from an intimate partner during their lifetime.

This high rate of violence against women needs special attention, and it can’t be ignored. Luckily, Dr. Shelley Lees and her colleagues at Mwanza Intervention Trials Unit (MITU) and the London School of Hygiene over the past 10 years have been working to find a solution to this common problem among women. This involves women attending in groups ten gender training sessions which were held in a convenient location within their community. This training was aimed to help them gain skills and knowledge to challenge physical and/or sexual violence from their male partners.

Recently, Dr. Lees and colleagues published part of their continuing work in the Journal of Culture, Health & Sexuality. This report provides information which helps to understand how gender training is helping women to change their attitudes and overcome violence. The study interviewed a subset of women who participated in a large trial implemented by MITU (called the MAISHA trial) to find out if it is possible to reduce violence among women in Mwanza city, Tanzania. From women’s views, gender training, which seeks to develop political awareness and transformation, can promote change amongst participants through a collective learning process. And this change brings a sense of confidence, worth, and power among women who participated in gender training to enable them to challenge violence.

The findings from this study bring hope to the fight to end violence against women in Tanzania.

Menstruation – the monthly genital bleeding experienced by women after reaching puberty – is a big problem among school girls in many parts of the world. Girls generally feel shame when the bleeding leaks on their school uniforms, get laughed at or teased by boys, lack soap, water or private places to change, clean or dry menstrual pads, or lack ways to reduce pains while at school. These problems have been reported to limit girl‘s participation in some school activities that require to stand or walk to the front of the class to answer a question or demonstrate something. They also cause girls to leave school early, miss some classes, stay at home during the days they are bleeding or leave school for good before the end of their school years.

MITU has received funds from the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) to carry out this study that will help address the problems related to menstruation and contribute in improved reproductive health.

Dr Elialilia Okello, a senior MITU research scientist, is leading this three-year study which will take place in eight secondary schools in Mwanza and Kilimanjaro regions. MITU will be implementing this study together with Femme International, a local non-governmental organisation working in Tanzania; the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, UK; and local government leaders in the two regions.

The study has three main stages. The first stage is the review of a health education programme implemented by Femme International and develop a plan to bring on board boys and local government leaders in the programme. This will help the boys and the leaders to understand issues related to menstruation and offer their support to girls during that period instead of laughing or teasing them. The study will recommend ways of giving out reusable sanitary pads at school and improving school water supply, toilet and hand washing facilities to help girls have the menstrual products, safe and private places to change or clean and dry the pads. The first stage will also include looking for ways to relief girls from pain during menstruation.

The second stage will involve researchers working with local government leaders and school teachers, to look at ways of including the improved health education programme in the routine school activities. The third stage will involve the assessment of the improved health education programme to see if it can be delivered in a long-term at lower cost, and is accepted by students, teachers and local government leaders. The programme will also be evaluated to see if it helps to change what girls do during their menstruation period and how they think about it.

Although the focus of this study is on problems related to menstruation among girls, it is expected that the boys will get a chance to understand issues related to menstruation as well as benefit from improved water supply, toilet and handwashing facilities at school. Apart from boys, the results are expected to benefit teachers, school officials and the general community. The study will also contribute in improved school participation and performance among school girls.

“During menstruation, girls are usually worried about the blood leaking into clothes while in class. A girl who stains her clothes in class is laughed at. Some girls experience severe pain and may need pain killers. Due to these problems girls may not be comfortable to attend a school with poor facilities or services to support them during this period” Dr Okello says. “Many times they miss attending school for several days each month and their performance may go down“

Dr Okello feels this study came at the right time. “In July 2017 I joined MITU to work in a research that was trying to assess if washing hands with soap every time school children used the toilet will help to reduce worm infection” she says. “The project gave me a chance to work within the schools. It is during this time that I realised that we needed to do more to help adolescent girls gain knowledge, skills and basic resources to manage their menstruation”

Continuing routine immunisations during the pandemic estimated to save more than 700,000 child lives from vaccine-preventable diseases

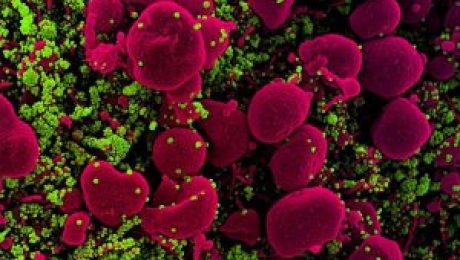

The health benefits of maintaining routine childhood vaccination programmes in Africa during the COVID-19 pandemic far outweigh the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission that might be associated with clinic visits, according to a modelling study published in The Lancet Global Health.

For every additional COVID-19 death that might be associated with additional exposure to the virus during routine clinic visits, the model predicts that 84 deaths in children before five years of age could be prevented by continuing with routine vaccinations. The additional risk of COVID-19 transmission associated with clinic visits is predicted to primarily affect older adults living in the same household as the vaccinated children.

The findings suggest that continuing with usual vaccination schedules could prevent 702,000 child deaths from the point of immunisation until they reach five years of age.

The study looked at all 54 countries of Africa and found that in all countries, the number of child deaths averted through vaccination far exceeded the number of excess COVID-19 deaths that might be associated with clinic visits.

However, the authors acknowledge there are other issues that will affect whether vaccination programmes can continue, such as vaccine supply chain problems or healthcare staff shortages during the pandemic.

Dr Kaja Abbas, joint lead author of the study, from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UK, said: “We found that, even with our most conservative estimates, the benefits of routine childhood immunisation in Africa are likely to far outweigh the risk of additional COVID-19 transmission that might ensue, and these programmes should be prioritised as far as logistically possible.”

National immunisation programmes are at risk of disruption due to the severe health system constraints associated with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and physical distancing measures introduced to mitigate transmission of the virus.

Researchers created a mathematical model to assess the risks and benefits of continuing with vaccination programmes during the current pandemic for all 54 countries of Africa. Their model assumes that the spread of COVID-19 in African countries will be similar to other countries that were affected earlier in the pandemic and were unable to control the virus. It estimates around 60% of the population will become infected and that the potential disruption to health services will last for six months.

Exact data on the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection associated with routine clinic trips for childhood immunisations were not available, so the model was based on assumptions relating to the likely number of people encountered during such a journey, both at the clinic itself as well as during travel there and back again. Risks to the child, accompanying adult and any household members were taken into account. The model also accounted for the household size and age composition in each country, as risk of death from COVID-19 is known to substantially increase with age.

The researchers based their estimates of the number of childhood deaths that could be prevented by routine immunisations on existing health data from each country. They focused on the impact of vaccines for diptheria, tetanus, pertussis, hepatitis B, Haemophilus influenzae type b and Streptococcus pneumoniae (bacterial causes of pneumonia and meningitis), rotavirus, measles, rubella, meningitis A and yellow fever. Vaccination rates for each country were assumed to be the same as in 2018.

According to the model, continuing with routine immunisation programmes may lead to 8,300 additional deaths across Africa (uncertainty interval 1,300 to 25,000), attributable to SARS-CoV-2 infections associated with children visiting immunisation clinics.

However, suspending such vaccination programmes to avoid excess COVID-19 deaths could lead to 702,000 children across Africa dying from preventable diseases before the age of five (uncertainty interval 635,000 and 782,000), according to the model. The researchers say this scenario assumes no catch-up vaccination campaigns at the end of the COVID-19 risk period and may overestimate the negative impact of suspending vaccination services for a short period of time.

Even in a much more conservative scenario (where suspending vaccination is primarily assumed to increase the chance of a local measles outbreak and children would be protected from other diseases from existing immunity in the population or catch-up immunisation campaigns at the end of the COVID-19 risk period), the number of childhood deaths that could be prevented was still greater than the potential increase in COVID-19 deaths for most countries of Africa.

Dr Tewodaj Mengistu, co-author of the study, from Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, Switzerland, said: “Routine immunisation programmes are facing enormous disruption across the globe due to this pandemic. Lockdowns make it harder for vaccinators and parents to reach vaccination sessions, health workers are being diverted to COVID-19 response, and misinformation and fear are keeping parents away. This important study shows just how big an impact this could have, risking the resurgence of diseases that vaccines have kept largely at bay.”

Findings were similar for all 54 countries of Africa, ranging from between 4 and 124 preventable child deaths in Morocco to between 28 and 598 in Angola, for each excess COVID-19 death. One third of vaccine-preventable deaths would be in Nigeria, Ethiopia, Democratic Republic of Congo and Tanzania, the study found. Around one third of vaccine-preventable deaths would be caused by measles, and another third would be attributable to pertussis, according to the model.

While the study clearly shows the health benefits of vaccination for children, it revealed that the additional risk of COVID-19 infections acquired during visits to the clinic would primarily affect adults from the same household. According to the model, 11% of excess COVID-19 deaths attributable to clinic visits are expected to affect parents or adult carers and 88% are predicted to affect older adults living in the same household as the vaccinated children. The researchers say this highlights the importance of shielding older adults to lower their risk of acquiring COVID-19, while children in their households can benefit from routine vaccinations.

Dr Stefan Flasche, senior author of the study, from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, UK, said: “We found that the biggest factors affecting the benefit of maintaining childhood immunisations during the pandemic are the likelihood of transmission of COVID-19 during clinic visits and the number of people encountered at the clinic. This highlights the need for personal protective equipment for clinic staff, the need to implement physical distancing measures and avoid crowded waiting rooms, and the importance of good hygiene practices to reduce virus transmission.”

The authors acknowledge that other factors must be considered when making decisions on sustaining routine childhood immunisation programmes during the COVID-19 pandemic. These include vaccine supply chain problems, reallocation of doctors and nurses to other prioritised health services, staff shortages resulting from ill-health or COVID-19 infection, and decreased demand for vaccination caused by fear of contracting COVID-19.

Dr Emily Dansereau, co-author and program officer at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, USA, said: “Across the African continent, many essential health services – from immunization to antenatal care to HIV and TB services – are experiencing significant challenges in the face of COVID-19. To address these new challenges and build resilient health systems, countries are exploring how to rethink health service delivery and are embracing innovative approaches to reach women, children and families with high quality support and care.”

Publication

Kaja Abbas*, Simon R Procter*, Kevin van Zandvoort, Andrew Clark, Sebastian Funk, Tewodaj Mengistu, Dan Hogan, Emily Dansereau, Mark Jit, Stefan Flasche, LSHTM CMMID COVID-19 Working Group. Routine childhood immunisation during the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa: a benefit–risk analysis of health benefits versus excess risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Lancet Global Health. DOI:10.1016/ S2214-109X(20)30308-9

What

The investigational antiviral remdesivir is superior to the standard of care for the treatment of COVID-19, according to a report published today in the New England Journal of Medicine. The preliminary analysis is based on data from the Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial (ACTT), sponsored by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the National Institutes of Health. The randomized, controlled trial enrolled hospitalized adults with COVID-19 with evidence of lower respiratory tract involvement (generally moderate to severe disease). Investigators found that remdesivir was most beneficial for hospitalized patients with severe disease who required supplemental oxygen. Findings about benefits in other patient subgroups were less conclusive in this preliminary analysis.

The study began on Feb. 21, 2020 and enrolled 1,063 participants in 10 countries in 58 days. Patients provided informed consent to participate in the trial and were randomly assigned to receive local standard care and a 10-day course of the antiviral remdesivir intravenously, developed by Gilead Sciences, Inc., or local standard care and a placebo. The trial was double-blind, meaning neither investigators nor participants knew who was receiving remdesivir or placebo.

The trial closed to enrollment on April 19, 2020. On April 27, 2020 (while participant follow-up was still ongoing), an independent data and safety monitoring board overseeing the trial reviewed data and shared their preliminary analysis with NIAID. NIAID quickly made the primary results of the study public due to the implications for both patients currently in the study and for public health. The report published today in the New England Journal of Medicine describes the preliminary results of the trial.

The report notes that patients who received remdesivir had a shorter time to recovery than those who received placebo. The study defined recovery as being discharged from the hospital or being medically stable enough to be discharged from the hospital. The median time to recovery was 11 days for patients treated with remdesivir compared with 15 days for those who received placebo. The findings are statistically significant and are based on an analysis of 1059 participants (538 who received remdesivir and 521 who received placebo). Clinicians tracked patients’ clinical status daily using an eight-point ordinal scale ranging from fully recovered to death. Investigators also compared clinical status between the study arms on day 15 and found that the odds of improvement in the ordinal scale were higher in the remdesivir arm than in the placebo arm. Trial results also suggested a survival benefit, with a 14-day mortality rate of 7.1% for the group receiving remdesivir versus 11.9% for the placebo group; however, the difference in mortality was not statistically significant.

Ultimately, the findings support remdesivir as the standard therapy for patients hospitalized with COVID-19 and requiring supplemental oxygen therapy, according to the authors. However, they note that the mortality rate of 7.1% at 14 days in the remdesivir arm indicates the need to evaluate antivirals with other therapeutic agents to continue to improve clinical outcomes for patients with COVID-19. On May 8, 2020, NIAID began a clinical trial (known as ACTT 2) evaluating remdesivir in combination with the anti-inflammatory drug baricitinib compared with remdesivir alone.

Article

J Beigel, et al. Remdesivir for the Treatment of COVID-19 – A Preliminary Report. The New England Journal of Medicine. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764 (2020).

Who

NIAID Director Anthony S. Fauci, M.D., is available for comment.

NIAID conducts and supports research—at NIH, throughout the United States, and worldwide—to study the causes of infectious and immune-mediated diseases, and to develop better means of preventing, diagnosing and treating these illnesses. News releases, fact sheets and other NIAID-related materials are available on the NIAID website.

Full publication : https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2007764

Disproportionate numbers of adults with chronic diseases, such as obesity, hypertension and lung disease, reduced their physical activity levels during the first weeks of the UK COVID-19 lockdown, according to a new study co-led led by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM),

Disproportionate numbers of adults with chronic diseases, such as obesity, hypertension and lung disease, reduced their physical activity levels during the first weeks of the UK COVID-19 lockdown, according to a new study co-led led by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM),

The research, conducted with UCL and the University of Bath, also found similar reduced levels of activity for people with disabilities and depression.

Published as a pre-print on medRxiv, the study uses data from a UK-wide online survey of more than 5,800 adults aged 20 and over, and reveals that while the majority (60%) of adults have maintained the same intensity of physical activity as they did pre-COVID-19, a quarter (25.4%) adopted lower intensity physical activity. This latter group included a bigger proportion of adults who have health conditions that heighten the risk of suffering from the most severe effects of COVID-19, should they contract the SARS-CoV2 virus.

Lead author of the study, Dr Nina Rogers (UCL Epidemiology & Public Health) said: “Low levels of physical activity put adults at increased risk of chronic diseases like obesity, cardiovascular disease and stroke which are also potential risk factors for more severe complications if someone develops COVID-19.

“It is concerning that in the mid to long term, multiple lockdowns might lead to prolonged periods of low physical activity which could increase the size of the population that is most vulnerable to severe complications from COVID-19.”

The study also found that not only people with medical conditions but also those who perceived themselves or others in their home to be at risk, had more frequently changed towards a more inactive lifestyle.

Senior author Dr Chrissy Roberts, Associate Professor at LSHTM said: “We believe that the trade-off between being protected from COVID-19 and the health detriments of reduced physical activity could place already vulnerable populations in a potential ‘no-win’ situation.

“When we’re talking about vulnerable people, it’s not just those who already have underlying health problems, but those who perceive themselves to be at risk too.

“We could well see seasonal cycles of COVID-19, as we do with flu. If that’s the case then we have to start thinking about protecting people from this COVID-19 epidemic, or the one that could come next year. If a person feels at risk now and reduces their physical activity in response, then this could set them on a course towards developing the same risk factors that would make them vulnerable to severe complications from COVID-19 in subsequent epidemic waves.”

Virologist Peter Piot, director of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, fell ill with COVID-19 in mid-March. He spent a week in a hospital and has been recovering at his home in London since. Climbing a flight of stairs still leaves him breathless.

Piot, who grew up in Belgium, was one of the discoverers of the Ebola virus in 1976 and spent his career fighting infectious diseases. He headed the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS between 1995 and 2008 and is currently a coronavirus adviser to European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen. But his personal confrontation with the new coronavirus was a life-changing experience, Piot says.

This interview took place on 2 May. Piot’s answers have been edited and translated from Dutch:

“ON 19 MARCH, I SUDDENLY HAD A HIGH FEVER and a stabbing headache. My skull and hair felt very painful, which was bizarre. I didn’t have a cough at the time, but still, my first reflex was: I have it. I kept working—I’m a workaholic—but from home. We put a lot of effort into teleworking at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine last year, so that we didn’t have to travel as much. That investment, made in the context of the fight against global warming, is now very useful, of course.

I tested positive for COVID-19, as I suspected. I put myself in isolation in the guest room at home. But the fever didn’t go away. I had never been seriously ill and have not taken a day of sick leave the past 10 years. I live a pretty healthy life and walk regularly. The only risk factor for corona is my age—I’m 71. I’m an optimist, so I thought it would pass. But on 1 April, a doctor friend advised me to get a thorough examination because the fever and especially the exhaustion were getting worse and worse.

It turned out I had severe oxygen deficiency, although I still wasn’t short of breath. Lung images showed I had severe pneumonia, typical of COVID-19, as well as bacterial pneumonia. I constantly felt exhausted, while normally I’m always buzzing with energy. It wasn’t just fatigue, but complete exhaustion; I’ll never forget that feeling. I had to be hospitalized, although I tested negative for the virus in the meantime. This is also typical for COVID-19: The virus disappears, but its consequences linger for weeks.

I was concerned I would be put on a ventilator immediately because I had seen publications showing it increases your chance of dying. I was pretty scared, but fortunately, they just gave me an oxygen mask first and that turned out to work. So, I ended up in an isolation room in the antechamber of the intensive care department. You’re tired, so you’re resigned to your fate. You completely surrender to the nursing staff. You live in a routine from syringe to infusion and you hope you make it. I am usually quite proactive in the way I operate, but here I was 100% patient.

I shared a room with a homeless person, a Colombian cleaner, and a man from Bangladesh—all three diabetics, incidentally,which is consistent with the known picture of the disease. The days and nights were lonely because no one had the energy to talk. I could only whisper for weeks; even now, my voice loses power in the evening. But I always had that question going around in my head: How will I be when I get out of this?

After fighting viruses all over the world for more than 40 years, I have become an expert in infections. I’m glad I had corona and not Ebola, although I read a scientific study yesterday that concluded you have a 30% chance of dying if you end up in a British hospital with COVID-19. That’s about the same overall mortality rate as for Ebola in 2014 in West Africa. That makes you lose your scientific level-headedness at times, and you surrender to emotional reflections. They got me, I sometimes thought. I have devoted my life to fighting viruses and finally, they get their revenge. For a week I balanced between heaven and Earth, on the edge of what could have been the end.

I was released from the hospital after a long week. I traveled home by public transport. I wanted to see the city, with its empty streets, its closed pubs, and its surprisingly fresh air. There was nobody on the street—a strange experience. I couldn’t walk properly because my muscles were weakened from lying down and from the lack of movement, which is not a good thing when you’re treating a lung condition. At home, I cried for a long time. I also slept badly for a while. The risk that something could still go seriously wrong keeps going through your head. You’re locked up again, but you’ve got to put things like that into perspective. I now admire Nelson Mandela even more than I used to. He was locked in prison for 27 years but came out as a great reconciler.

I have always had great respect for viruses, and that has not diminished. I have devoted much of my life to the fight against the AIDS virus. It’s such a clever thing; it evades everything we do to block it. Now that I have felt the compelling presence of a virus in my body myself, I look at viruses differently. I realize this one will change my life, despite the confrontational experiences I’ve had with viruses before. I feel more vulnerable.

One week after I was discharged, I became increasingly short of breath. I had to go to the hospital again, but fortunately, I could be treated on an outpatient basis. I turned out to have an organizing pneumonia-induced lung disease, caused by a so-called cytokine storm. It’s a result of your immune defense going into overdrive. Many people do not die from the tissue damage caused by the virus, but from the exaggerated response of their immune system, which doesn’t know what to do with the virus. I’m still under treatment for that, with high doses of corticosteroids that slow down the immune system. If I had had that storm along with the symptoms of the viral outbreak in my body, I wouldn’t have survived. I had atrial fibrillation, with my heart rate going up to 170 beats per minute; that also needs to be controlled with therapy, particularly to prevent blood clotting events, including stroke. This is an underestimated ability of the virus: It can probably affect all the organs in our body.

Many people think COVID-19 kills 1% of patients, and the rest get away with some flulike symptoms. But the story gets more complicated. Many people will be left with chronic kidney and heart problems. Even their neural system is disrupted. There will be hundreds of thousands of people worldwide, possibly more, who will need treatments such as renal dialysis for the rest of their lives. The more we learn about the coronavirus, the more questions arise. We are learning while we are sailing. That’s why I get so annoyed by the many commentators on the sidelines who, without much insight, criticize the scientists and policymakers trying hard to get the epidemic under control. That’s very unfair.

“My lung images finally look better again. I opened up a good bottle of wine to celebrate, the first in a long time.”–Peter Piot, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

Academics at the University of Oxford and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), working on behalf of NHS England and in partnership with NHSX, have analysed the pseudonymised health data of over 17.4 million UK adults to discover the key factors associated with death from COVID-19.

This is the largest study on COVID-19 conducted by any country to date, analysing NHS health data from 17.4 million UK adults between 01 February 2020 and 25 April 2020, which has given the strongest evidence to date on risk factors associated with coronavirus. Among the sample, there were 5,707 deaths in hospitals attributed to COVID-19.

Compared to white people, people of Asian and Black ethnic origin were found to be at a higher risk of death. Previously, commentators and researchers have reasonably speculated that this might be due to higher prevalence of medical problems such as cardiovascular disease or diabetes among BME communities, or higher deprivation. The findings, based on detailed data, show that this only accounts for a small part of the excess risk. Consequently, further work must be done to fully understand why BME people are at such increased risk of death.

Additionally, people from deprived social backgrounds were also found to be at a higher risk of death, which also could not be explained by other risk factors.

Results confirmed that men are at increased risk from COVID-19 death, as well as people of older ages and those with uncontrolled diabetes. People with more severe asthma were also found to be at increased risk of death from COVID-19.

The study linked data about patients that had been hospitalised with COVID-19 with data held in primary care records processed by TPP. This was carried via the OpenSAFELY analytics platform, a new secure mechanism which allowed the GP records to be linked where they are stored for individual care. This minimises the security risks associated with transferring and storing data elsewhere, to deliver analyses quickly and safely while preserving patient privacy. All identifiable data remains in control of the NHS and data is pseudonymised before it can be accessed by researchers.

Professor Liam Smeeth, Professor of Clinical Epidemiology at LSHTM, NHS doctor and co-lead on the study, says: ‘We need highly accurate data on which patients are most at risk in order to manage the pandemic and improve patient care. The answers provided by this OpenSAFELY analysis are of crucial importance to countries around the world. For example, it is very concerning to see that the higher risks faced by people from BME backgrounds are not attributable to identifiable underlying health conditions’.

Dr Ben Goldacre, Director of the DataLab in the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences at the University of Oxford, NHS doctor and co-lead on the study, says: ‘During a global health emergency we need answers quickly and accurately. That means we need very large, very current datasets. The UK has phenomenal coverage and quality of data. We owe it to patients to keep their data secure; and we owe it to the global community to make good use of this data. That’s why we have developed a new highly secure model, taking the analytics to where the data already resides.’

Further analyses using OpenSAFELY are already underway, including investigation into the effects of specific drugs routinely prescribed in primary care. The platform can also be used to evaluate COVID-19 spread with innovative approaches to modelling; predict local health service needs; assess the indirect health impacts of the pandemic; track the impact of national interventions; and inform exit from lockdown.

China is facing growing pressure from national governments and international organizations to open its doors to an independent, international investigation into the origins of the novel coronavirus causing the current COVID-19 pandemic, as well as into the nation’s early response to the outbreak. So far, however, the Chinese government has given no public sign it is interested in cooperating. Its silence, and signs that China is stifling origins research by its own scientists, have fueled theories that the virus accidently leaked from a lab there.

“The whole world wants the exact origin of the virus to be clarified,” German Minister of Foreign Affairs Heiko Maas told reporters today, endorsing calls for China to allow an outside body to conduct field research and other studies aimed at determining how severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus that causes COVID-19, jumped into humans. The Chinese government’s response to such calls, he says, will demonstrate “how transparent it wants to be with the virus.”

The remarks echo those made in the past few weeks by the European Commission, Sweden, Australia, and others. And they come as a few government officials, including U.S. President Donald Trump and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, have asserted that the virus escaped from a laboratory in Wuhan, China, where SARS-CoV-2 was first identified. That lab studies and stores samples of coronaviruses found in bats and other species. So far, however, the assertions that the new virus was in that facility have not been backed by hard evidence, and some scientists are skeptical of the escape claim, saying it is more likely that SARS-CoV-2 naturally emerged elsewhere.

Still, both politicians and scientists are increasingly calling on China to make any investigations it is conducting into the matter more transparent—and to allow independent scrutiny. After its Friday meeting, for example, the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) Emergency Committee, a group of independent scientific experts advising the agency, recommended a probe that included “field missions” to China, and perhaps the involvement of the World Organisation for Animal Health and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Its goal would be to “identify the zoonotic source of the virus and the route of introduction to the human population, including the possible role of intermediate hosts,” the panel said.

“We need transparency,” Ursula von der Leyen, president of the Commission, said this past Friday on CNBC in response to a question about whether she would support an independent review. But she suggested any investigation would need China’s participation and could wait until the pandemic abates.

Sweden’s health minister, Lena Hallengren, made similar remarks on 30 April. “When the global situation of COVID-19 is under control, it is both reasonable and important that an international, independent investigation be conducted to gain knowledge about the origin and spread of the coronavirus,” she wrote to Sweden’s Parliament. Hallengren said Sweden is planning to ask the European Union to push for the probe.

Australia wants to see WHO push for an investigation. “It would seem entirely reasonable and sensible that the world would want to have an independent assessment of how this all occurred, so we can learn the lessons and prevent it from happening again,” Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison said on 23 April, urging WHO members to back an inquiry.

WHO is not currently involved in studies in China, spokesperson Tarik Jasarevic tells ScienceInsider, but it “would be keen to work with international partners and at the invitation of the Chinese government to participate in investigation around the animal origins” of the virus.

“It is our understanding that a number of investigations to better understand the source of the outbreak in China are currently underway or planned,” he added, “including investigations of human cases with symptom onset in and around Wuhan in late 2019, environmental sampling from markets and farms in areas where the first human cases were identified, and detailed records on the source and type of wildlife species and farmed animals sold in these markets.”

The Chinese government has said it has launched its own investigation into the origins and early response to the pandemic, but has publicly provided few details. And it has responded with anger to assertions it bears responsibility for allowing the outbreak to spread globally, with government-sponsored news organs calling such claims “baseless.” Multiple press reports have also provided evidence that China has promoted disinformation campaigns suggesting the virus originated in other places, such as the United States.

The first trial, called DISCOVERY, started on 22 March 2020 to test four experimental treatments against COVID-19. This trial will recruit 3200 patients from Belgium, France, Germany Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. The second trial, called RECOVERY, started enrolment of patients in the United Kingdom on 27 March 2020. This trial is testing two treatments against COVID-19. In the future, RECOVERY trial will be expanded to assess the impact of other potential treatments as they become available.

The first trial, called DISCOVERY, started on 22 March 2020 to test four experimental treatments against COVID-19. This trial will recruit 3200 patients from Belgium, France, Germany Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. The second trial, called RECOVERY, started enrolment of patients in the United Kingdom on 27 March 2020. This trial is testing two treatments against COVID-19. In the future, RECOVERY trial will be expanded to assess the impact of other potential treatments as they become available.

For more information follow the links below:

https://presse.inserm.fr/en/launch-of-a-european-clinical-trial-against-covid-19/38737/